Activities

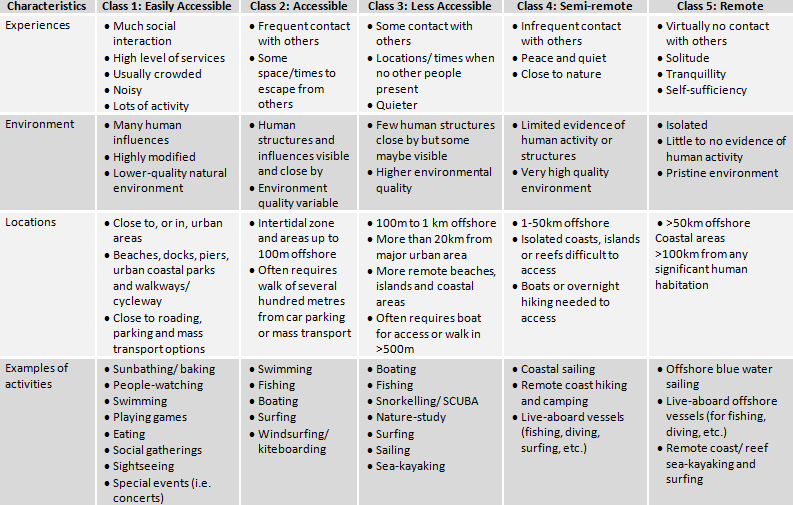

There is a wide range of recreation and tourism activities that New Zealand’s marine environment supports. Few locations now remain inaccessible due to the wide availability of new technologies. 0afa5679-84f2-4406-aa62-1b6fa5919d3b The Spectrum of Marine Recreation Opportunities 56dd9de1-cb00-4bad-8cf3-0c7701e55dd1 (SMARO), as shown in the figure below, is a model that helps to categorise marine recreation and tourism experiences relative to their distance from shore and from human settlements. This model can be used to assist with understanding the range of experiences, and potential impacts that these activities are having, or are likely to have.

In terms of patterns of use of marine areas for recreation and tourism, the SMARO model shows that both the intensity of use and the diversity of activities have an inversely proportional relationship with distance from both the shoreline (that is, both intensity and diversity decrease further offshore) and places of human settlement. Thus urban beaches and near-shore locations are the most intensively used and offshore locations distant from cities and towns the least intensively used. This suggests that different management approaches will be required for the various types of marine environments as classified by proximity.

Research completed in 2012 showed that this pattern is generally true for New Zealand’s marine environment with the notable exception of tourism “hotspots”, such as Milford Sound and the Poor Knights Islands, and locales that offer specific recreational experiences, such as the popular surfing breaks in Raglan, Ahipara and South Taranaki.

5ec41f43-01f5-43cc-819d-ab190d3122eb

The following sections describe marine recreation and tourism activities in more detail.

Swimming

Swimming at the beach only became a popular recreational activity in New Zealand at the end of the 19th century. Prior to that, the marine area was perceived as dangerous, few Europeans could swim, and many people drowned. In the late 1880s medical authorities in New Zealand championed the health benefits of swimming. By the early 20th century, sea bathers were forming organisations to improve the image of swimming and provide amenities such as changing rooms at the beach. It was during this time that the increasing popularity of beach swimming saw a rise in surf lifesaving as both a voluntary service and competitive sport. As a consequence, beach swimming became safer and even more popular. c4bcb52d-3dc0-4c96-8ae0-e16ade93f66f Today, the beach lifestyle is an integral part of the national way of life and highly valued by New Zealanders and visitors, particularly during the summer months.

Surfing, board-sailing, kite-boarding, stand-up-paddle boarding and surf-skiing

Surfing is believed to have originated from Hawai’i. The well-known Hawaiian surfer Duke Kahanamoku toured New Zealand in 1915 giving surfing demonstrations in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch. 69c7ad65-5286-4dba-b3a1-ef2b78001d39 Locals were inspired and surfing became established in those areas. Surfing as a widespread recreational activity only became established in New Zealand in the 1960s. It was during that decade, that the growth of the surfing and hippy culture really gained momentum, as it spread from California to Australia and then to New Zealand. Several New Zealand coastal towns become strongly associated with surfing, and the related surfing and beach lifestyle, including Whangamatā, Mount Maunganui, Raglan, New Plymouth, Gisborne and Ahipara

In 2013 the New Zealand Herald reported that more than 200,000 Kiwis and 30,000 tourists surf in New Zealand. 593f26c7-a69f-4a3d-a15e-50a78385d408 It has become a way of life for many people living around the coast. As a consequence of the strong popularity of surfing, and threats to high quality surf-breaks from development, organisations such as the New Zealand Surf Break Protection Society have been advocating for legal protection of surf-breaks. Some surf breaks now have statutory protection under the NZCPS. The idea of installing artificial surf reefs to promote and increase opportunities for surfing was popularised in New Zealand during the 1990s.

Wind-surfing or board-sailing began in the early 1970s and, in a pattern typical of the invention of a new marine recreational activity, its popularity grew and the activity diversified. There is now general recreational wind-surfing, wave-sailing, slalom racing, speed sailing and Olympic competitions. Kite-surfing (also known as kite boarding) has developed with similar speed since the early part of the 21st century and more recently stand-up-paddle boarding has grown rapidly. Competitive sporting events, recreational activities and commercial hire and tourism operations now exist for all of these marine recreational activities in New Zealand.

Diving and snorkelling

People have always had a keen interest in going beneath the sea. Ancient manuscripts contain depictions of early divers and century old artefacts imply that people dove to gather materials for jewellery. In the 19th century people began to use diving bells, supplied with air from the surface, probably the first effective means of staying underwater for any length of time.

acebd914-4052-408d-91d8-89d645845eff

The invention of the SCUBA (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus) in 1943 changed the way the world saw the underwater world, and increased the demand for ways that people could explore the marine environment. The Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI) is the world’s largest recreational diver training organisation, with members teaching the vast majority of the world’s recreational divers, issuing nearly 1,000,000 certifications each year.

7d535229-3fe0-42bc-92cc-cb4fd5963700

New Zealand is a popular dive destination and is rated as having some of the top dive spots in the world. The protection offered by marine reserves has helped ensure that some key locations have remained attractive for diving. Jacques Cousteau, the famous marine explorer, rated the Poor Knights Islands (now a fully protected marine reserve) as one of the top ten dive spots in the world. More recently, the marine reserve was named in CNN’s top 50 dive sites, because it has some of the best sub-tropical underwater gardens on the planet. The Rainbow Warrior, a vessel deliberately sunk off the Northland coast to create an artificial reef and dive site, was named by The Telegraph, a major newspaper in the United Kingdom, as one of their top dive sites. 6780fcbd-9f2e-4834-8fcc-3dcde7109155 The creation of artificial reefs, through the deliberate sinking of boats or other materials, is increasingly being used in New Zealand to create or enhance dive locations.

Snorkelling, where a mask and snorkel (usually also with fins for propulsion and safety) is used to view underwater, is also a very popular activity. It is an accessible and budget-friendly way for people to see and enjoy the marine environment and is commonly offered to a wide range of age groups at resorts and on charter boats throughout the world. Snorkelling in New Zealand is very popular particularly over the summer months. With a coastline of over 15,000 kilometres 54c10210-c72c-49f7-8626-a7839b83198d there are many prime snorkelling spots offering people free and easy access. A number of marine reserves around the coast provide both diving and snorkelling opportunities. Examples include the Cape-Rodney-Okakari Point (Goat Island) Marine Reserve, the Tāwharanui Marine Reserve and the Te Whanganui-A-Hei (Cathedral Cove) Marine Reserve.

Boating

New Zealand has a long maritime nautical history which extends back to the first humans to arrive on these shores. Polynesian peoples represent one of the greatest ocean explorer cultures and their navigation and settlement of the widely dispersed South Pacific Islands is evidence of their abilities. This tradition continued from the arrival of the first Māori over 800 years ago. In an island country with a very rugged topography, the coastlines and numerous harbours, inlets, estuaries and connected rivers and lakes provided critical transportation routes. Māori used these extensively, and took advantage of the large hardwood indigenous trees such as totarā and kauri to build many different types of waka (canoes) for transport, trade, warfare, ceremony and recreation.

Early European explorers and settlers also arrived via sea-born vessels (sailing ships and then steamers). Similarly, they found it easier to move around the country via the coast, harbours, estuaries and rivers than overland. The ready supply of large and easily accessible trees that produced rot resistant wood (such as kauri) suitable for marine use also contributed to the dominance of sea-born craft during the early part of New Zealand’s European history. This was particularly the case in Auckland and Northland, where the country’s boat-building industry was concentrated. Early designs mirrored those of sailing vessels from Europe, but very quickly were modified to suit local conditions. Mullet boats were designed as fast, small, shallow-draught yachts which could be used to net mullet in shallow estuaries and then quickly sail the catch back to port. Prior to the development of roads, large sailing barges, called scows, were used to transport people, cattle, timber, aggregate and other goods and produce between the numerous isolated settlements dotted around the coast.

The first organised yacht racing occurred as part of the anniversary day regattas held each year to commemorate the establishment of the major settlements in New Zealand. The Auckland Anniversary Regatta became established as a yacht racing event during the 1850s. Initially, commercial vessels were used for the competitions, but by the 1870s, boats were being built specifically for racing. Two boatbuilding Auckland-based families, the Bailey’s and the Logan’s, fiercely competed for over 60 years to design and build the fastest boats, and they produced some of the best racing yachts in the world. Several of their yachts have recently been restored and still race.

Yacht racing and pleasure cruising was supported by the numerous yacht clubs which quickly became established in all the main settlements. The earliest was the predecessor to the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron which was established in 1871. Initially the clubs focused on organising racing events, but later they sought to promote the sport by teaching children and youth to sail in smaller sailing dinghies. The development of plywood and marine glues after World War II encouraged a generation of New Zealanders to build their own boats and head out onto the water in launches, sailing dinghies and cruising yachts.

From the 1960s the invention and use of a range of materials such as fibreglass for hulls, alloy for masts and dacron for sails transformed boating in New Zealand by making craft more sea-worthy, reliable and affordable. During the past two decades, the wide availability of much improved navigational equipment such as the GPS chart-plotter, has facilitated safe cruising further afield. Boats now provide the platform for a wide variety of marine recreational activities including fishing, diving, water-skiing/wake-boarding, sightseeing, racing and wildlife watching. Boats also provide a means of transport to previously inaccessible islands, reefs, harbours and beaches.

fe29bd4a-d274-462e-afd9-ef4b79535150

Yachting and motor-boating has continued to develop in New Zealand, both as a competitive sport and a recreational activity. There is a large cruising boating community throughout the country. A New Zealand Marine Industry Association assessment of boat ownership in 2010 estimated the number of boats in New Zealand to be above 470,000 (including 5000 charter and tour boats).

5c8eba05-3b61-4664-9b0a-e30934e760f3

In 2011 Maritime New Zealand commissioned market research on recreational boat ownership which indicated that 19 per cent of New Zealanders owned at least on boat at the time of the survey.

8a06de49-3479-4dbb-83b2-ceca85ff66c6

The relatively protected and safe harbours around the upper North Island, such as the Bay of Islands, Hauraki Gulf, and in the South Island, such as the Marlborough Sounds, are a boating paradise. Increasingly the offshore islands and remote cruising destinations are becoming more popular, as technology allows people to travel further, more comfortably and safely in their boats. In addition, New Zealand (particularly the north-eastern part of the North Island) has become a favoured destination for blue-water yacht cruisers. These international tourism arrivals, while low in terms of volume, have had significant impacts on the coastal communities such as Ōpua, Russell, Whangarei and Auckland.

Whilst it has a long history, particularly in the Arctic and Northern Canada, where its use spans at least 5,000 years, sea kayaking has only recently become a widespread marine recreational activity. This growth mirrors that of boating more generally, as kayaks began to be constructed out of durable materials such as polyethylene plastic, which were mass-produced from moulds, and therefore could be sold at affordable prices. Tourism New Zealand promotes kayaking as one of the best ways to explore New Zealand's coastline and inland waterways. The activity is popular with both private recreational kayakers and commercial tour operators who offer sea-kayaking tours in many places such as the Nelson Lakes National Park, the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, the Bay of Islands Marine Park, the Marlborough Sounds and the Coromandel Peninsula.

The use of personal water craft (jet-skis) has also become a popular marine activity, with significant growth in both high powered, manoeuvrable single person craft and those that are suitable for multiple riders. They are used for activities as diverse as fishing, water skiing, wakeboarding, surf riding and tow-in surfing (where surfers are towed in to surf large waves by jet-skis). In addition, a wide diversity of watercraft are being designed and utilised in the sea including radio-controlled yachts and power-boats, waka-ama, dragon-boats and other paddle-powered craft, submersibles, semi-submersibles, specialist wake-boarding boats, offshore powerboats (for racing), large expedition designed and equipped cruising boats, jet-boats, and super-yachts.

Fishing

Kaimoana, or food from the sea, has always been an important component of Māori culture. It is significant as a source of sustenance, as a good to be traded, and as part of the hospitality provided when hosting guests. Other New Zealanders have also used the sea as a source of food, and have fished to both supplement diets and for pleasure, from the time that Europeans first arrived on these shores.

Recreational fishing remains extremely important and this activity takes many forms, including:

- Fishing from rocks or from human made structures

- Surfcasting from beaches

- Using spears to catch fish such as flounder in shallow tidal areas

- Using set nets

- Hook and line fishing

- Trolling using lures of live baits from boats

- Spear-fishing (either free-diving or using diving gear)

- Rock-lobster (crayfish) hunting

- Shell-fish gathering (in inter-tidal areas, using dredges, via digging and via diving and snorkelling)

- taking marine life from rocks, rock-pools and the inter-tidal zone

Before the 1960s, most land-based fishing spots were reached using bicycles and walking. Four-wheel motorbikes, trail bikes, 4WD vehicles and helicopters have now allowed people to access difficult-to-reach and remote spots. Rapid developments in boating, diving, navigation and fishing technology has also allowed recreational fishers to access more remote fishing grounds, further from shore, and in deeper areas.

Big game fishing is now a major part of the recreational fishing and boating industry, with charter boats offering week-long trips to some of New Zealand’s most remote fishing spots. New Zealand is well known around the world for its bill-fish (e.g. striped marlin), tuna fisheries, as well as the opportunities to fish for species such as snapper, kahawai, hāpuka, bluenose and trevalli.

Marine mammal and seabird interactions

Because of its isolation and huge latitudinal variation (extending from the sub-tropics to the subantarctic) the extended islands of New Zealand have been important breeding locations for sea-birds (New Zealand has been termed the ‘sea-bird capital of the world’) and for migratory marine mammals, such as the Southern Right Whale. New Zealand has a high level of endemism in sea-birds (such as the Yellow-eyed Penguin and Fiordland Crested Penguin), coastal birds (e.g. Northern Dotterel and Auckland Islands Cormorant) and in marine mammals (for example the Hector’s and Maui’s dolphins and the New Zealand Sealion). Early human settlement of New Zealand made extensive use of these animals and significant industries were based on whales, fur-seals and sea-lions and a variety of sea-birds (e.g. shearwaters or ‘muttonbirds’). In many cases, these animals were hunted until their populations became mere remnants of their pre-human numbers.

More recent protection of these creatures has created, in some cases, the opportunity to develop a new wildlife industry based on the idea of visiting and observing them, as a tourist attraction. dfabaf79-aabe-4197-8d51-30125d7429d9 Such activities have become extremely popular in New Zealand over the past three decades and marine wildlife-based tourism is now the dominant form of marine tourism in the country.

In New Zealand, this is a wide-ranging sector, which includes dolphin watching and swimming (snorkelling with dolphins), whale watching, remote underwater sea life watching, seabird viewing and, increasingly, shark-diving encounters. There are a number of permits issued for companies to provide marine mammal and seabird interactions from land, boats and air-based platforms around the country. There are dolphin-based tours nationwide, and whale-based tours in the Hauraki Gulf (Bryde’s whales) and Kaikōura (sperm whales). It is worthwhile noting that New Zealand no-longer permits the holding of dolphins in captivity, however, some pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) remain in zoos (such as Auckland Zoo).

Cruise ships

New Zealand has seen a phenomenal growth in the cruise ship industry, of over 250 per cent during the last five years, making cruise arrivals the third largest inbound market for New Zealand tourism. 67028e66-c8a7-403f-84d5-ee74b897c857 The New Zealand cruise season runs from September through to March. During the 2012-2013 cruise season, New Zealand received over 210,000 cruise passenger arrivals and more than 80,000 crew. 6caafdbb-2618-4c09-aa44-647197a8e068 The cruise ship industry is an economic contributor to a number of New Zealand ports particularly Auckland, Tauranga, Wellington, Akaroa, and Port Chalmers (Dunedin). Cruise ships also visit a number of remote New Zealand coastal locations such as White Island, Fiordland, Stewart Island (Rakiura) and New Zealand’s subantarctic Islands.

Cruise passenger behaviour has been steadily shifting from organised tours to free and independent travellers. This change of behaviour means a shift in the demand for activities from these cruise passengers. Whilst most of these tend to be shore-based, increasingly there is demand for marine-based activities in the location of stop-over.

Special events and sporting contests

Many coastal locations are deliberately establishing special events to encourage visitation (and the commensurate economic and social benefits) to their venues. Seafood festivals, fishing contests, surfing competitions, sand-sculpting contests, beach volleyball championships, sailing regattas, multi-sport races, music concerts and wildlife festivals are examples of a multitude of deliberately staged events which encourage tourism from participators and spectators alike.

7584e66c-5e5b-4b61-957b-38a5365b62b2

The use of the coast for special events has intensified in recent years. From the Auckland Anniversary Regatta to the seafood festival in Kaikōura and fishing events in Bay of Islands, the country’s marine resources are being used as a basis for a wide range of events. Many of these are competitive sporting events, such as the State Ocean Swim Series, or for festivals and hospitably events, such as the Whitianga Scallop Festival which is one of New Zealand’s most popular seafood events. Smaller communities often host local music festivals using the beach as a ‘party’ base. The Ōhope Beach concert at Mahy Reserve is just one example of where locals come together to enjoy local musicians and a family picnic at the beach.

One particular growth area is the spread of marine adventure-type challenges that are extreme in nature. Rowing or paddling across significant bodies of water (such as Cook Strait and Fouveaux Strait), traversing remote coastal areas on foot, surfing off-shore ocean reef waves, solo boating voyages and deep diving (including breath-hold diving) are examples of the growing range of extreme activities which attempt to provide adventure, challenge and deliberately place participants at a higher perceived risk of injury or death. Such activities have been growing in popularity and profile and this trend is likely to continue. fff8a2f3-0168-4c6f-a7d1-62ffb93f0b7f

General coastal and beach activities

There are many other activities that do not fall into the above categories. These include the increasing popularity of walking along the coast which has seen major infrastructure investment such as the development of coastal walkways (e.g. paved pathways, board-walks and trails) around New Plymouth, Napier and Ahuriri Estuary, Ōrewa, Ōmaha, Tamaki Drive and the Auckland Viaduct Harbour and Wynyard Quarter re-development.

Sunbathing and relaxing at the beach is hugely popular and there are many destinations around the country, both busy and peaceful, where people head to enjoy this activity. Sandy beaches close to areas of population are the most intensively used coastal locations. A good example is the beach at Mount Maunganui, which was voted as New Zealand’s 2014 top beach by Tripadvisor users, and is a very popular place for sunbathing, people-watching, playing games and picnicking. Additional activities which take place on the inter-tidal zone on beaches and rocky shores include walking dogs, land-yachting, beach volleyball, beach cricket, touch and other ball sports, horse riding, motor-bike and off-road vehicle use, exploring rock-pools, jogging/running, cycling and other forms of exercise, kite-flying, sand-castle and sand sculpture creation, photography, painting, tai-chi, yoga and many others.

Holiday homes

New Zealand has a long tradition of coastal holiday dwellings. Traditionally these were rudimentary structures with little infrastructure and few services (for example, no electricity, telephone, sewage and waste water services, or ‘town’ water supply). The stereo-typical Kiwi bach (or crib) was a small basic structure built close to a beach, with an outside ‘long-drop’ toilet and tank water collected from the roof. Because New Zealand’s summer coincides with the public holiday period of Christmas and New Year, and the long school holiday break, lengthy periods of living at the bach (often shared by extended family groups and friends) over this holiday period became synonymous with the Kiwi summer lifestyle.

Over the past three decades, the growing population, urbanisation and improved transportation (both roads and vehicles) has seen coastal properties within two to three hours’ drive of a city become highly sought after. This demand has led to an escalation of coastal property prices, a commensurate investment in coastal dwellings, structures and infrastructure and a major transformation of the New Zealand coast. Traditional baches within two hours drive of a city are now rare. Larger, more luxurious holiday homes are now the norm and a number of coastal communities have become upmarket coastal resort-type developments, some complete with canal and marina front properties. Examples include Pauanui, Matarangi, Whangamatā, Ōmaha, Marsden Cove and Tutukākā.

What is clearly evident from this transition, and the financial inflation that has resulted, is how highly valued the coastal lifestyle is for New Zealanders. In a clear and almost uniform pattern, the monetary value of property increases the closer it is to the coast and waterfront, and properties with sea views attract premium prices. Proximity to the sea and all the opportunities it offers, both from a passive perspective (seeing, smelling and hearing the sea) and an active point of view (such as walking, swimming, fishing and boating ), are hugely attractive to New Zealanders and highly valued by them.

-

Orams, M B and M Lück, in press

-

Originally developed by Orams in 1996 and further refined by Orams and Lück in 2013

-

Cessford G, et al., 2012

-

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/lifesaving-and-surfing

-

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/lifesaving-and-surfing/page-4

-

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10912395

-

http://marinebio.org/oceans/scuba/

-

Project AWARE Foundation, 2009

-

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/picturegalleries/7300359/The-worlds-top-ten-dive-sites.html?image=9

-

http://www.doc.govt.nz/Documents/science-and-technical/docts10.pdf

-

Orams M B, 1999, 17

-

Beca, 2012

-

Beca, 2012

-

Orams M B, 1999, 25

-

http://www.cruisenewzealand.org.nz/about/

-

http://www.cruisenewzealand.org.nz/about/

-

Orams, M B and M Lück, in press

-

Orams, M B and M Lück, in press

Last updated at 2:11PM on February 25, 2015