Decision-making process

Regional council planning

Regional councils have responsibility for controlling the use of land for the purpose of maintaining coastal water quality and coastal marine ecosystems 647d65bc-de0c-496e-9a22-a5c33286975b and controlling discharges into water bodies b26199d2-750e-4998-b64d-cba8c2ce15e0 . This includes managing the negative effects of sedimentation and pollutants, which are derived from land-based sources and which end up being discharged into the marine area. Regional councils prepare regional policy statements and regional plans to address the issue. Some regional councils prepare separate plans, which specifically address issues such as sedimentation and discharges from dairy farms to help them effect their obligations under the RMA. In practice it has proved easier to deal with point source pollution under the RMA than non-point source pollution.

There are two main approaches that regional plans take in relation to avoiding or minimising impacts of land use on the marine area:

- One method employed by a number of regional councils is to classify coastal receiving waters and to apply appropriate water quality or sediment quality standards to those waters. This is a more “effects based” approach, in that any consequent land use activity could be expected to at least consider the effects of the activity on the relevant receiving water quality or sediment quality standard. This allows innovation on behalf of the consent holder as to what site management practices or controls could be implemented. Water quality standards which are linked to rules will have a more direct effect on outcomes than standards linked to policies.

- Another method is to focus more on the land use activity itself and apply methods to control or regulate these types of activities. For example, if a rural catchment is identified as having a negative impact on the ecological health of the marine area because of the high levels of sedimentation, and the main causes are identified as forestry and farming activity, the regional plan might include rules to mitigate these effects, such as requiring stock to be kept out of waterways and preventing harvesting in riparian areas.

These methods can combined - such as those relating to land uses being linked to water quality standards.

Non-point source pollution poses more of a challenge for regulators, because it is not caused by isolated and identifiable acts which are generally more easily controlled by the consent process. Regional councils are responsible for identifying the environmental effects of both urban and agricultural run-off, and implementing regional solutions and management. To discharge this duty, councils may produce technical guidelines for the management of stormwater systems and sediment control programmes. They may also set up incentive programmes and form community-based groups to encourage farmers, forestry companies and other users to alter the way they use their land to minimise the effects of run-off. There are opportunities to undertake stronger actions on these issues, including through new regional plans prohibiting intensification in some areas, requiring farm environmental management plans, and requiring planting/harvesting plans for forestry.

Integrated catchment management plans

Catchment management plans are a tool to integrate the management of natural resources and the protection of community values. Such a management approach is an established concept used around the world. However, in the past they have tended to focus on the planning and management of a catchment. In recent years the focus has widen to include the coastal receiving environment for that catchment.

f537b1fa-a5f3-4580-aa80-9e8f65d2d333

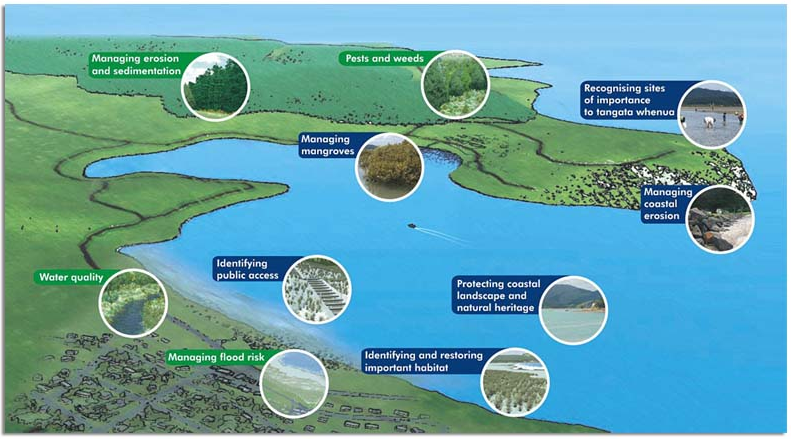

Harbour and catchment management planning focuses on managing land and water together to achieve long-term outcomes which are beneficial to the wider environment. Such a tool considers the values and uses of a catchment and integrates them with the multiple stakeholders, issues and objectives into one overarching plan, as highlighted by the figure below. Such types of planning documents are non-statutory but have the capacity to inform and support statutory documents such as district and regional plans.

Māori have long been advocates for catchment management planning, particularly in regards to coastal issues. 3e4faa01-91d2-4275-b63b-04d750292c54 There are a number of tools used for this purpose, including taiapūre and mātaitai, which are increasingly being used as part of managing a wider catchment. These tools are discussed in Chapter 4: Kaitiakitanga. The success of catchment management planning lies in the engagement of the community and key agencies to support and implement the actions needed. f661c3cf-99e8-4ab1-ae0c-f5aabd12f6e5 This is discussed further in a case study below.

There are a number of best practice elements for catchment management planning that have been identified by research, including:

f938b78f-ad3c-4b79-8fb4-3ce2826a30ae

.

e5272447-6526-45b5-b38b-3e53c1c53bb5

- Political leadership and multi-agency co-operation

- Cross sector collaboration

- Inclusion of iwi and community aspirations and drivers

- Robust science

- Improved capacity building and action on the ground

- Provision of adequate resourcing for both planning and implementation phases

- Good governance and clear institutional frameworks

- Monitoring and evaluation of outcomes that leads to adaptive management

- The presence of a strong catchment manager or champion

A summary of the outcomes from the 10-year Integrated Catchment Management for the Motueka River programme identified a number of issues that were addressed during the programme b1471e83-6d1a-44ba-baa2-4da3db210232 as shown in the table below.

Topic | Issues addressed |

|---|---|

| Allocation of scarce water resources among competing land and instream uses |

|

| Managing land uses in harmony with freshwater resources |

|

| Managing land and freshwater resources to protect and manage marine resources |

|

| Integrative tools and processes for managing cumulative effects |

|

| Building human capital and facilitating community action |

|

Territorial authorities

Under section 31 of the RMA, territorial authorities are responsible for controlling the effects of land use outside the coastal marine area, and this includes downstream effects on the marine environment. Territorial authorities can prepare district plans to address these issues. Whereas regional councils tend to focus on catchment-wide issues, territorial authorities focus more on site development issues such as earthworks and the construction of impervious areas.

District plans can indicate the amount of impervious area (building or paving) that a property can have, and property owners who wish to exceed this limit must apply to the territorial authority for consent to do so. Territorial authorities and their local network operators also have responsibility for stormwater infrastructure in their area, such as maintenance and replacement of stormwater pipes, maintaining stormwater pumping systems and outfalls, construction of silt traps and detention ponds.

Territorial authorities undertake monitoring and mapping, to identify any issues associated with localised flooding and overland flow, as well as any pollution-related issues. The Local Government Act 2002 requires them to undertake assessment of the water and sanitary services in their district, including wastewater and stormwater, to assess amongst other things whether they pose a danger to public health.

Reporting water pollution

Most regional and territorial authorities have a 24 hour pollution hotline, which can be called if pollution of the catchment occurs, and which can be found on council websites. Pollution response teams respond to reports of pollution events, and aim to put an immediate halt to the discharge, ensure that polluted waters are cleaned up and collect evidence of the pollution incident.

When an incident occurs, the regional council can send a warning letter setting out how the perpetrator has breached either the rules of a regional plan or the RMA. Then the council can issue an abatement notice requiring the perpetrator to stop the offending activity occurring or take some action to ensure compliance. The council can issue infringement fines of up to $1000 or prosecute the offender. The maximum penalties for offenders are up to two years in prison or a fine of up to $300,000, with a further $10,000 for every day that the offence continues. The maximum penalty for a commercial organization is $600,000, with a further $10,000 for every day that the offence continues. The Environment Court can issue an enforcement order requiring the offender to comply with the RMA. 57acbfe1-3a34-4e7d-bec8-9f509fe45034

-

RMA 1991 section 30(1)(c)

-

RMA 1991 section 30(1)(f)

-

http://www.aucklandcity.govt.nz/council/documents/technicalpublications/TR2009-092.pdf

-

Feeney C, W Allen, A Lees and M Drury, 2010

-

Waikato Regional Council, 2010

-

http://www.aucklandcity.govt.nz/council/documents/technicalpublications/TR2009-092.pdf

-

Feeney C, W Allen, A Lees and M Drury, 2010

-

Fenemor A, 2013

Last updated at 2:11PM on February 25, 2015