Case study: Sea Change

New Zealand’s first marine spatial plan was completed in December 2016. It was the result of a three-year Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari project that focused on addressing the growing spatial resource conflicts and ecological degradation associated with the Hauraki Gulf.

The Hauraki Gulf covers 1.2 million hectares of ocean, stretching from Mangawhai in the north to Waihi on the Coromandel Peninsula and hosting New Zealand’s largest city. It is one of this country’s most prized marine resources, for many reasons. The Hauraki Gulf generates more than $2.7 billion every year in economic activity and supports the greatest number of recreational fishers and boaties in the country. It has a particularly rich diversity of seabirds, marine mammals, fisheries and marine habitats. In addition, it provides a wide variety of sanctuaries, marine reserves and islands. The Hauraki Gulf was designated a marine park in 2000.

0548ea83-c4c7-45be-b661-a5af65a108e1

The Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari project had its inception in the 2011 State of our Gulf Report 5cb5f06a-ffba-4ae4-96ea-021b1dec762d released by the Hauraki Gulf Forum. This reported that “the Gulf is experiencing ongoing environmental degradation, and resources are continuing to be lost or suppressed at environmentally low levels.” In addition, through taking a historical perspective on the changes to the state of the Gulf over time, the report was able to highlight “the incredible transformation the Gulf has undergone over two human lifespans”. The report made it clear that current management approaches were ineffective in addressing the scale of the challenge and that a step change was required to turn the situation around.

The preparation of a marine spatial plan was seen as a mechanism through which all the significant issues impacting on the Gulf could be considered together as an integrated whole. It also provided the opportunity for mana whenua and stakeholders to be placed at the centre of the process through the adoption of a collaborative process. A collaborative process is a powerful mechanism through which stakeholders gain an understanding of each other’s values and perspectives, jointly scrutinise available scientific information, and seek to develop joint solutions.

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari Process

A 16-member Project Steering Group (PSG) was established to oversee the project with members consisting of eight representatives of the statutory bodies involved in managing the Gulf and an equal number of Mana Whenua representatives, thereby putting in place a co-governance structure. The PSG was led by Mana Whenua and agency co-chairs. The overall role of the PSG was ‘to provide leadership, strategic oversight, challenge, testing and guidance’ to the SWG; as well as to ‘nurture, protect and support’ the SWG. The PSG was to receive and approve the plan developed by the SWG and advocate implementation to the respective agencies. The project was supported by a Project Board which managed the overall project budget, logistics and technical support.

The plan itself was developed over three years by a Stakeholder Working Group (SWG) with representatives from commercial fishing, recreational fishing, farming, aquaculture, infrastructure, community and environmental interests. Four positions were made available to Mana whenua. The balance of the members were determined through public meetings, where the sector groups were asked to put forward their preferred representatives. These initial selections were tested with other sector groups to ensure that the people nominated were able to work across sectors in a collaborative manner.

The role of the SWG, as set out in the Terms of Reference, was to ‘compile information and evidence, analyse, represent all points of view, debate and resolve conflicts and work together as a group to develop a future vision for a healthy and productive Hauraki Gulf. This includes identified preferences for the allocation of marine space. The future vision will be manifested as a physical document – the Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan.’ The group was to operate on a consensus basis which means that ‘every member either supports or does not actively oppose (can live with) the decision.’ da6492d1-015c-4e46-a74f-cdfe009c9d0c

The SWG first convened in December 2013, and met approximately monthly up until late 2016 when the plan was completed, with a break of several months during mid-2015. This break, or ‘pause’, was generated by concerns held by some parties as to how the plan writing was shaping up prior to the expected deadline of June 2015. It resulted in an extension of the deadline and some reconfiguring of the technical support team.

A high degree of trust developed between the SWG members and by the end of the process the group operated as a tight team. The collaborative approach enabled SWG members to become well-informed about the issues affecting the Gulf and possible solutions, helped develop social capital between the sectors, and encouraged members to provide sector information that would normally be withheld under an adversarial process. An Independent Chair, who was not a member of the SWG or PSG, was appointed by the PSG to facilitate the group. Two people held this position during the course of the project. Neither were professional facilitators, but were both respectively senior members of the accounting and legal professions.

During the early stages of the project, six ‘Roundtables’ were established to focus the plan development work on key elements of the overall picture as well as to involve a broader range of stakeholders. These included more of those potentially affected by the plan provisions including farmers, foresters, aquaculturalists and national representatives of the fishing industry. The topics for the Roundtables were fish stocks, water quality and catchments, aquaculture, biodiversity and biosecurity, accessible Gulf (the ability of people to access and experience the Gulf), and Gulf infrastructure. Two co-chairs were appointed for each Roundtable, both who were SWG members.

The Roundtables met for approximately one day a month for six months and operated on a broad consensus basis. Members endeavoured to agree on a vision and problem definition, and then focused on developing solutions to the problems identified. The timeframe for the operation of the Roundtables was short, particularly for the development of trust between members required for collaboration to work. The meant that, in most cases, only high-level solutions were developed; controversial issues, such as marine protection, were referred back to the SWG for consideration as part of the integration process. The reports prepared by the Roundtables were not formally agreed to by all members and were not publicly released. They formed the building blocks of the plan with the material further developed by the SWG.

Early on in the project planning stages, it was agreed that the plan would be science based as well as incorporating Mātauranga Māori. Scientists from a range of research institutions presented their work directly to the SWG and Roundtable meetings and their presentations were uploaded onto the project website. It was also agreed that the plan would be based on existing scientific knowledge as there was not the time or budget to commission new work. This proved largely to be the case although one new piece of research was commissioned to examine benthic recovery in the cable protection zone. In addition, during the project, the Waikato Regional Council and Dairy NZ commissioned work to review and synthesise current knowledge about the impacts of sediment and nutrient flows into the Firth of Thames. dc2376e5-4dc5-4113-a269-b65f9b1401fa

An extensive public process was undertaken alongside the SWG and was geared to the front end of the project. This involved public meetings, 25 ‘Listening Posts’ 83d8cf81-bbfc-4518-a6ba-1e253995c9d7 , a web-based use and values survey 29b356cd-5848-492b-adfa-29f54433d711 , a survey on Roundtable topics and a second one on priority issues identified by Roundtables 898119f0-c610-49dc-8f41-45ce894d2b03 and an active website and email updating programme. In addition a ‘Love Our Gulf’ event and social media campaign was undertaken. This public engagement effort connected with more than 14,500 people overall, with 9,350 actively contributing their views to the project fa3ecc6c-6cbf-49f3-8849-0d567503be53 . The results of the engagement were summarised and made available to the SWG members to inform plan development.

A group of community stakeholders who had been present at meetings held to select the SWG members, called the ‘Hauraki 100+’, were convened every few months so that the SWG could provide an update on progress, discuss key issues and obtain feedback from the broader community. The group was intended to act as a ‘sounding board’ for the SWG during the preparation of the marine spatial plan.

A Technical Support Group comprising agency staff provided a range of science, planning and communications expertise to the SWG and Roundtables. Central and local government agencies, led by the Department of Conservation, assembled spatial data sets on a web-based tool called SeaSketch. Seasketch had been developed by researchers and software developers based at the University of California Santa Barbara. A standby GIS and SeaSketch technical sub-group was established to assist with SWG and Roundtable mapping requirements as they emerged. A plan writing team was initially formed in the beginning of 2015 (when the plan was originally to be delivered in June of that year). As the focus on producing the content of the plan increased in the latter stages of the project, a reconfigured core plan writing group was established, headed by an independent lead writer and two science advisors.

The project was overseen by an Independent Review Panel comprising 5 experts in various fields including Paris-based Charles Ehler who was the co-author of the UNESCO guide to marine spatial planning. The Panel was supported by a function lead and support staff. The Panel provided three reports and the recommendations helped to inform the PSG on how well the project was progressing as well as to guide the further development of the plan by the SWG. fc4c0eb5-7e0d-411d-b372-b47d09493daa

Content of marine spatial plan

The resultant plan is structured around four parts, or kete (baskets) of knowledge: Part One Kaitiakitanga and Guardianship; Part Two Mahinga Kai – Replenishing the Food Baskets; Part Three Ki Uta Ki Tai – Ridge to Reef or Mountains to Sea; and Part Four Kotahitanga – Prosperous Communities b1aaa6e4-5c0d-4428-ac43-8ca33ec85dec . The front end of the plan consists largely of objectives and actions, and is supported by a summary of the scientific basis underpinning the plan provided in the appendices. The plan is wide-ranging and detailed. Some key features are described below but the reader is encouraged to read the plan proper. It can be found here.

The fish stocks chapter was based on two broad strategies, first to apply an ecosystem-based approach to harvest management, and second to put in place mechanisms to protect and enhance marine habitats, thereby increasing the ecological productivity of the Gulf. Restoration of marine habitats focuses on a nested approach. Large benthic areas are to be protected through the retirement or mitigation of key stressors, such a fishing gear impacts, to allow natural regeneration. Smaller areas within these zones will be the focus of passive restoration (through the establishment of marine reserves) and active restoration through the transplanting of species or establishment of new habitat patches. cdbf52e5-2305-479e-85e3-c1f1aa020ba2

The chapter also included a proposal to remove seabed damaging fishing methods from the Gulf including bottom trawling, Danish seining and dredging. This was to prevent any further habitat damage, reduce sediment resuspension and allow natural or assisted recovery of the three-dimensional benthic habitats which are of critical importance to the survival of many juvenile fish. Fishers will be assisted to transition to methods such as long-lining which produce higher quality fish, achieve a higher market price, and have less environmental impacts. d05b7cae-bb65-4a95-aef7-2bdf74e993c4

A novel proposal in the plan is the creation of Ahu Moana co-management areas. These will be located in nearshore areas extending one kilometer seawards. They will be co-managed jointly by Mana Whenua and local communities, to mobilise and focus the energy and knowledge of these parties, towards improving the management of local fisheries and inshore coastal waters. This will help strengthen customary practices associated with the marine space, as well as more effectively control harvest levels, particularly in areas under increasing pressure from the growing Auckland population. 1e9d247d-fe3f-4371-bc49-4d76c80e45f7

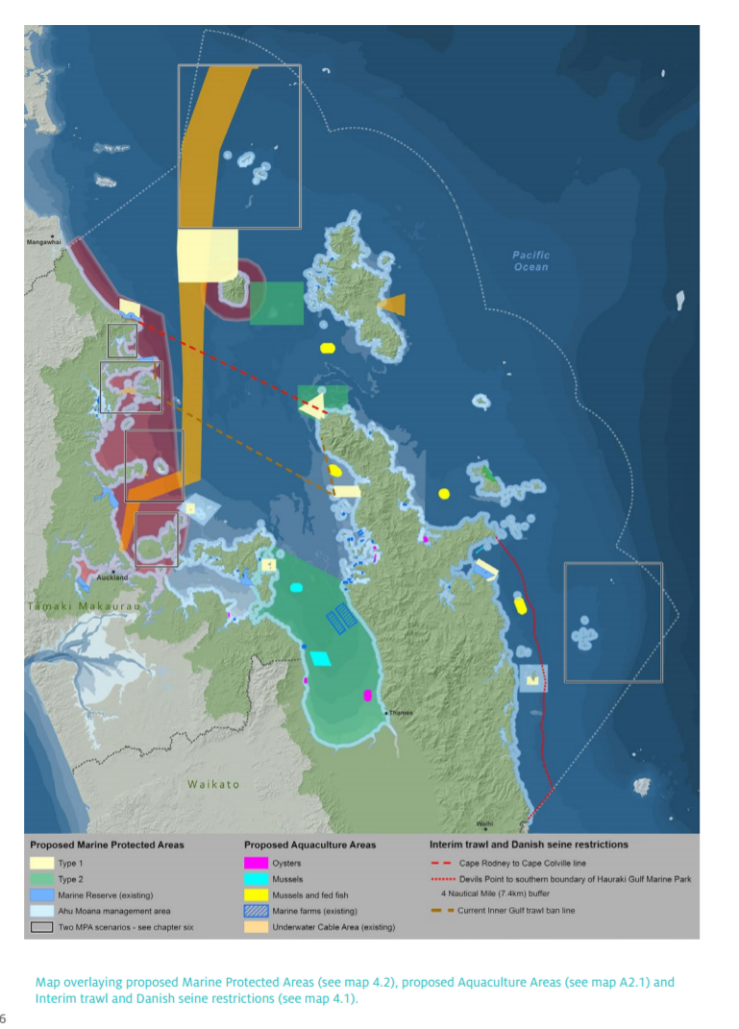

The plan identifies 13 new aquaculture areas and 13 new protected areas as well as an extension in size of two existing marine reserves. In addition, an extensive area is identified as being unsuitable for aquaculture due to its proximity to the Auckland metropolitan area where there are many potentially conflicting uses of the water space.

The provision of marine protection was one of the more difficult issues to reach consensus on, and in some cases this could not be achieved in the time available. As a result, two alternative proposals are included for some specific sites. Provision has been made for customary harvest and the adverse effects on commercial fishers will need to be addressed. In addition, there is to be a 25-year review of the protected areas, and co-governance and management of them once established. 1a964737-847d-435c-af2d-728714095987

The impact of poor water quality on the ecological health of the Hauraki Gulf, was one of the greatest areas of concern, with the main stressor being sediment. bf779afb-1e90-4141-a922-a285f423c910 Sediment is a difficult issue to effectively address, due to the large number of diffuse sources that contribute including conservation land, forestry, agriculture, earthworks and stream bank erosion. In addition, a large amount of sediment has already reached the marine area, and is retained in the Gulf for long periods of time, being regularly re-suspended by wave action.

The approach set out in the plan is wide ranging and includes measures to reduce soil erosion, to minimise sediment entering water ways and to stabilise sediment once it has reached the marine environment. Some of the key features of the strategy are to develop catchment management plans (starting with four high priority catchments), establish catchment sediment limits, increase sediment traps through reinstating natural or engineered wetland systems, ensure the adoption of good sediment practice by all land users and retire inappropriate land use on highly erodible land. Emphasis has also been put on scaling up one-on-one interaction with farmers through doubling resources to employ additional land management officers. 857bf46d-8f92-48e9-aa88-2783af809452

Nutrient enrichment was an emerging water quality issue in the Firth of Thames. The rivers discharging into the area have high nutrient loadings primarily as a result of intensive dairying within the catchment. The Firth of Thames is not well flushed and the water becomes stratified in late summer and early Autumn. Water quality monitoring in the outer Firth has identified oxygen depletion and seawater acidification during these times. 3fb4ce49-f31b-4a52-838e-d966bb9a72fd The plan places a cap on nitrogen discharge levels which are to be kept at or below current rates until sufficient scientific work had been completed to enable an appropriate nutrient load limit to be put in place. 83c61024-419b-4ab8-8205-09937098960a

Key learnings from Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari

Key learnings from the process were drawn from key informant interviews in a Case Study Report. 10 in-depth interviews were held with a range of people involved in the science and Matauranga Maori elements of the project. This included science advisors, a Mātauranga Māori advisor, members of the Independent Review Panel, members of the Project Board, and a Mana Whenua member of the Stakeholder Working Group (SWG). The focus of the interviews was on the information interface with the project, but comments made by interviewees on other elements of the project were also recorded and have been reported here.

Integration of Mātauranga Māori

- Mātauranga Māori can provide valuable input on values as well as long-term scientific knowledge based on observation and experience.

- Effective integration of Mātauranga Māori takes time and therefore is unlikely to be achieved in a process with short timeframes.

- Advance work to develop Mātauranga Māori input, prior to the planning process commencing, can help avoid being in a catch-up mode.

- Accessing Mātauranga Māori information is likely to be resource intensive.

- Creating a separate Mātauranga Māori workstream can be successful in focusing effort but requires effective measures to integrate that work into the broader project.

- Developing protocols around confidentiality and intellectual property can be important in enabling information to be accessed.

- Including Mana Whenua support people in the writing and GIS teams can help integrate material as the plan is prepared.

Role of Science

- Science can be used to help frame the project in its initial stages. One way to achieve this is through undertaking a scientific review before the collaborative planning process commences.

- Appointing a Chief Scientist for project can help focus the scientific contribution into a project.

- Using a small group of scientists for the duration of the project as conduits between the SWG and the broader scientific community can be effective.

- Scientific effort and funding needs to be deployed towards developing basis ecological datasets to support marine spatial planning efforts.

- Spatial data software, such as Seasketch, can be too complex for laypeople to feel comfortable with and fully utilise.

- Spatial data should be integrated into the project from the outset.

- Scientific information needs to be synthesised and applied to the relevant management questions.

- SWG members need to be educated in how to deal with scientific uncertainty and relevant tools should be deployed, such as risk assessments.

- Social and economic information should be brought into the process.

- Modelling can be useful to test the social and economic impacts of potential solutions.

- Marine spatial plans can usefully set out a research plan for priority research going forward, to support agency prioritisation and funding applications by science institutions.

- Collaborative processes can be important learning experiences for scientists.

Linkage with ecosystem-based management

- Marine spatial planning can help apply ecosystem-based management to the marine area.

- The concepts inherent in ecosystem-based management are generally well aligned with Mātauranga Māori.

The collaborative process

- Collaborative processes can be very powerful in mobilising diverse stakeholders around common agreed solutions.

- Collaborative processes can be very challenging and resource intensive for all parties involved and they create a lot of uncertainty and risk.

- Collaborative processes can be particularly challenging for the statutory agencies that sponsor them.

- Collaborative processes provide a powerful learning environment for participants which can change their understandings of the world.

- There is a danger that vocal/powerful people can dominate processes and that the outcomes represent watered-down compromises.

- It is important that the SWG represents a wide range of relevant interests.

- Consideration needs to be given to the ongoing role of SWGs in championing the plan as well as monitoring and adapting it.

- Collaborative processes can create particular challenges for Mana Whenua participants due to the time commitment involved and the need to ensure adequate Mana Whenua representation on sub-groups.

- Collaborative processes take time, and imposing unrealistic timeframes on them can derail the process.

- Care is needed to build strong relationships between the sponsoring/implementing agencies and the SWG

- Agencies can provide valuable technical input into the process and also help to test the practicality of potential solutions.

- Including an independent review panel provides a useful check on the process as well as substantive input.

The spatial plan

- Marine spatial plans that are prepared through collaborative processes are unlikely to be perfect.

- Producing a fully-fledged marine spatial plan is a tall order, and a phased approach may be more feasible where the initial plan is further developed at a later stage

Applicability of approach to other marine areas

- Marine spatial planning has been shown to be a successful approach in the Hauraki Gulf which is the most complex marine area in the country, and so is likely to be of considerable value, and more easily applied, in other marine areas.

5ce6fd21-36d7-4e3f-a749-4af9892077d5

-

http://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/en/planspoliciesprojects/plansstrategies/seachange/Pages/home.aspx

-

Hauraki Gulf Forum, 2011b

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2013, p. 2-4

-

Green M. and J. Zeldis, (2015) Firth of Thames Water Quality and Ecosystem Health: A synthesis, Hamilton: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research.

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2014.

-

Jarvis R. M., B. B. Breen, C. U. Krägeloh and D. R. Billington (2015) ‘Citizen science and the power of public participation in marine spatial planning’, Marine Policy, 57, pp.21-26

-

Perceptive Research (2015) Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari summer survey 2014-2015: Results and Analysis, http://seachange.org.nz/PageFiles/774/FINAL%20REPORT%20summer%20survey%202014-2015.pdf

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, undated, p. 2

-

Independent Review Panel (2014) First Review Report, 21 August, http://seachange.org.nz/PageFiles/500/IRP%20first%20review%20report.pdf

Independent Review Panel (2015) Second Review Report, 17 March, http://seachange.org.nz/PageFiles/500/Independent%20Review%20Panel%20second%20report%20March%202015.pdf

Independent Review Panel (2016) Final Report, 12 September, http://seachange.org.nz/PageFiles/500/IRP%20Final%20Review%20Report%20Final%2012%20Sept%202016.pdf

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2016

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2016, p. 71.

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2016, p. 74-75.

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2016, p. 52-54.

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2016, p. 124-126

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2016, 133-134

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2016, p. 134-141

-

Green and Zeldis, 2015, 40 & 49

-

Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari, 2016, p. 145-146.

-

Peart.R (2017) Sea Change Tai Timu Tai Pari Case Study

Last updated at 4:15PM on February 9, 2018